The Problem

STORMWATER

Stormwater runoff carries trash, bacteria, �and pollutants from the urban environment into nearby bodies of water.

Heavier rains and storm surges — which are predicted to occur more frequently due to global warming — can cause erosion and flooding, damaging habitats, property, and infrastructure.

In Rhode Island, stormwater runoff causes algal blooms that contaminate usable and drinking water supplies.

Current Solution

WHAT WE DO NOW

In terms of stormwater management, traditional systems of pipes and water treatment facilities typically move water long distances for treatment.

When there’s more than an inch of rain, the city’s capacity for stormwater management is overwhelmed and raw sewage, along with untreated stormwater, overflows into rivers and Narragansett bay. As the frequency of intense storms increases due to climate change, this will become more and more problematic.

New Solution

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

Green infrastructure interventions reduce the stormwater going into the system by treating and absorbing it. Such projects takes advantage of natural elements and processes to manage water in urban environments, including Providence.

Examples of green infrastructure include planter boxes, rainwater harvesting systems, permeable pavements, and tree canopies. Rain gardens, such as the garden pictured in the illustration above, feature vegetation with deep root systems planted in a shallow depression to collect stormwater runoff from urban areas.

Project Location

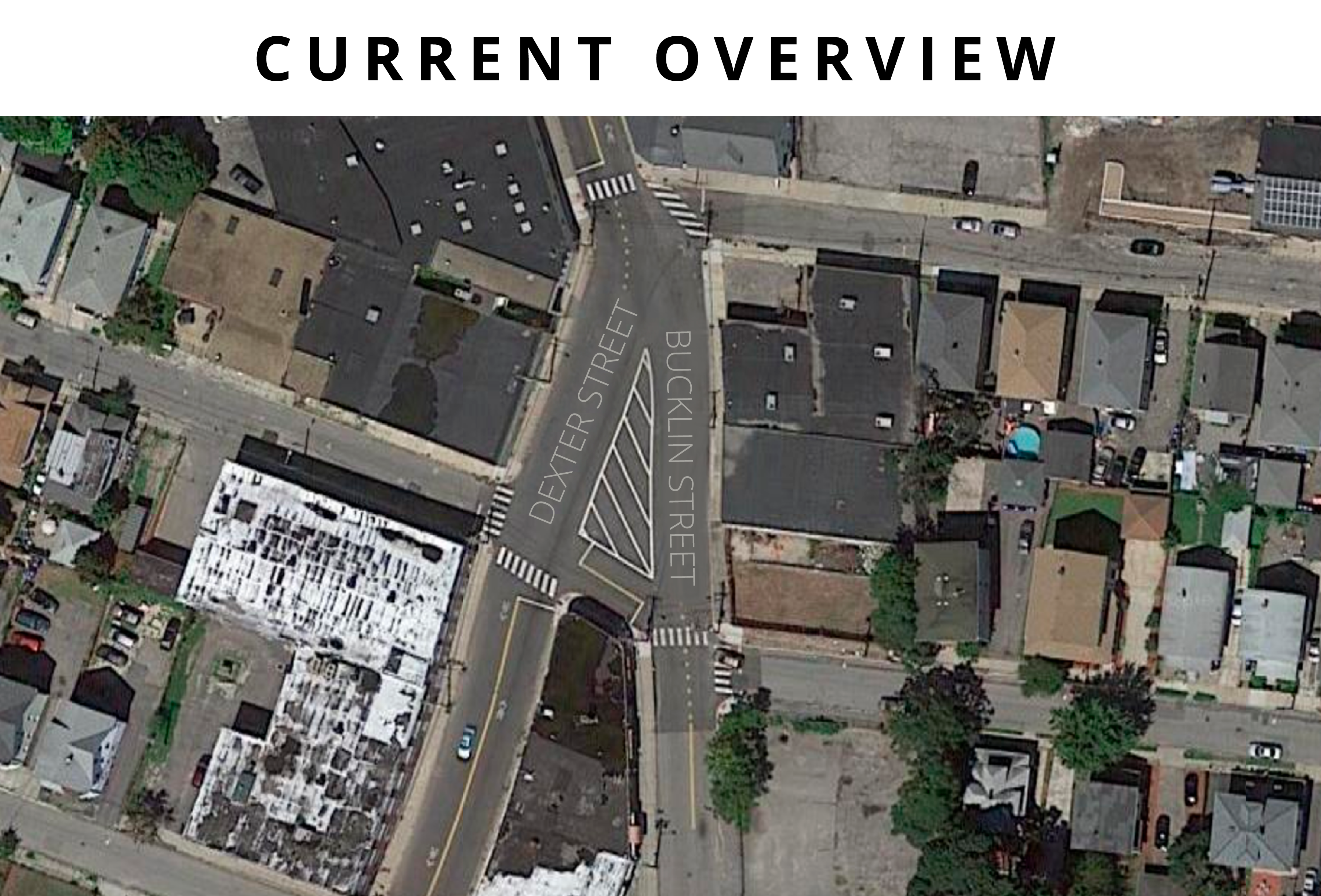

SELECTING A SITE

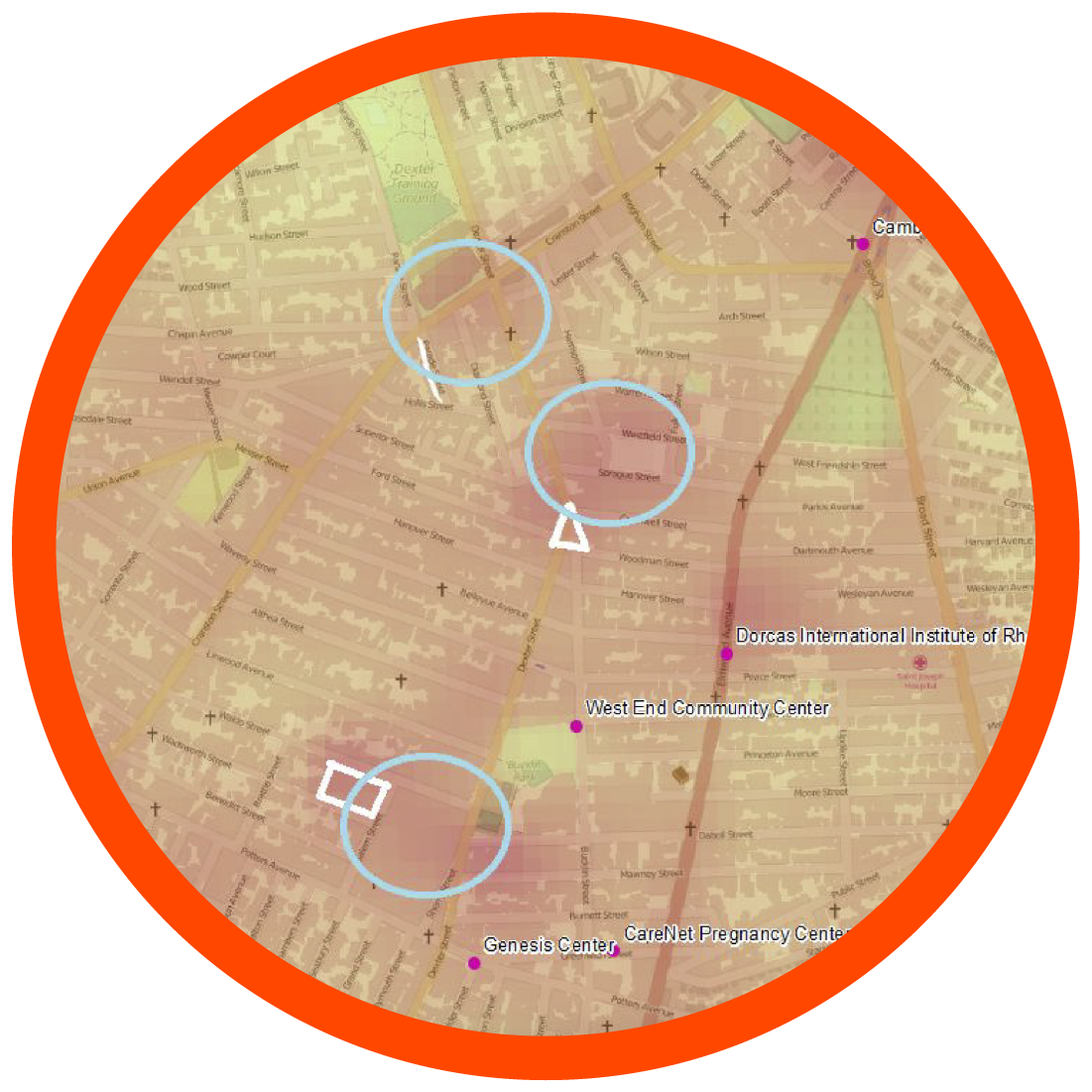

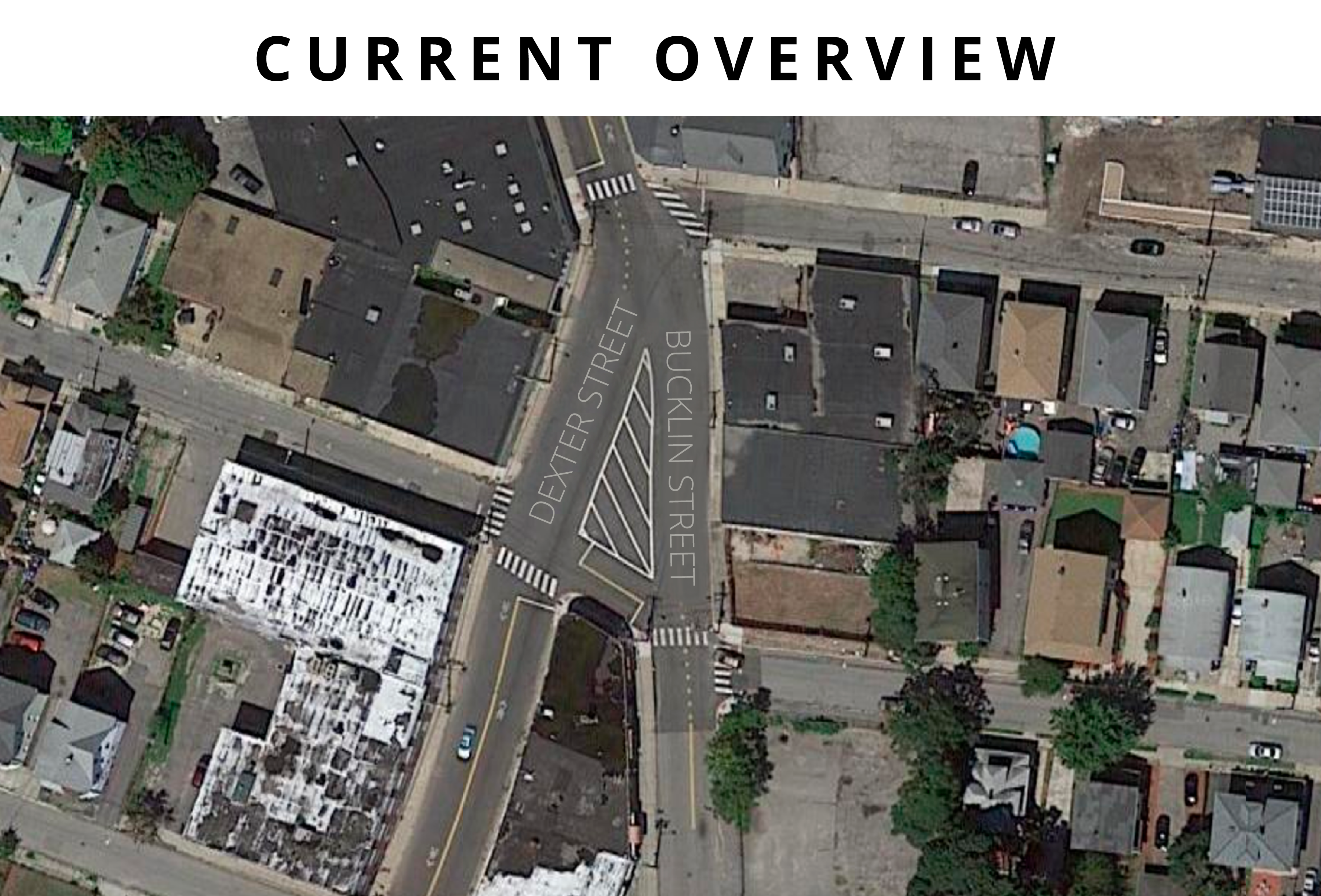

Janice, Kai, and Grace were given a set of potential areas of focus through the Brown TRI-Lab program. All of the potential sites were local, limited to communities in Providence. The team selected the Dexter and Bucklin intersection as their green infrastructure project site. Below, the site can be seen from an aerial view with traffic patterns demarcated.

Through map data and anecdotal evidence, they identified the zone �as a problematic intersection with significant �traffic issues, no green space, and observed �flooding. In addition, its proximity to residential �areas, schools, and neighborhood gathering sites made it a worthwhile location for an intervention.

Methods

COLLECTING DATA

-

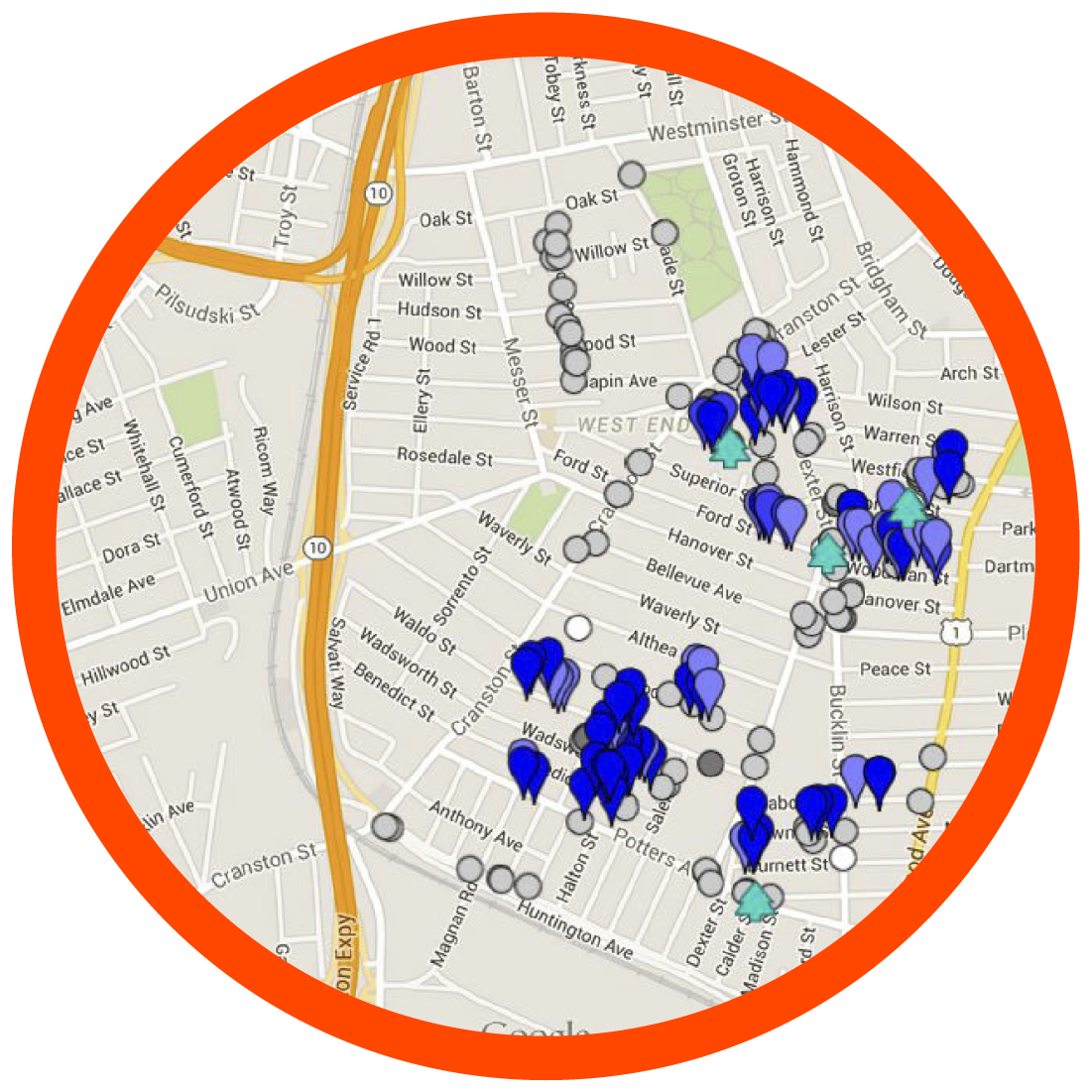

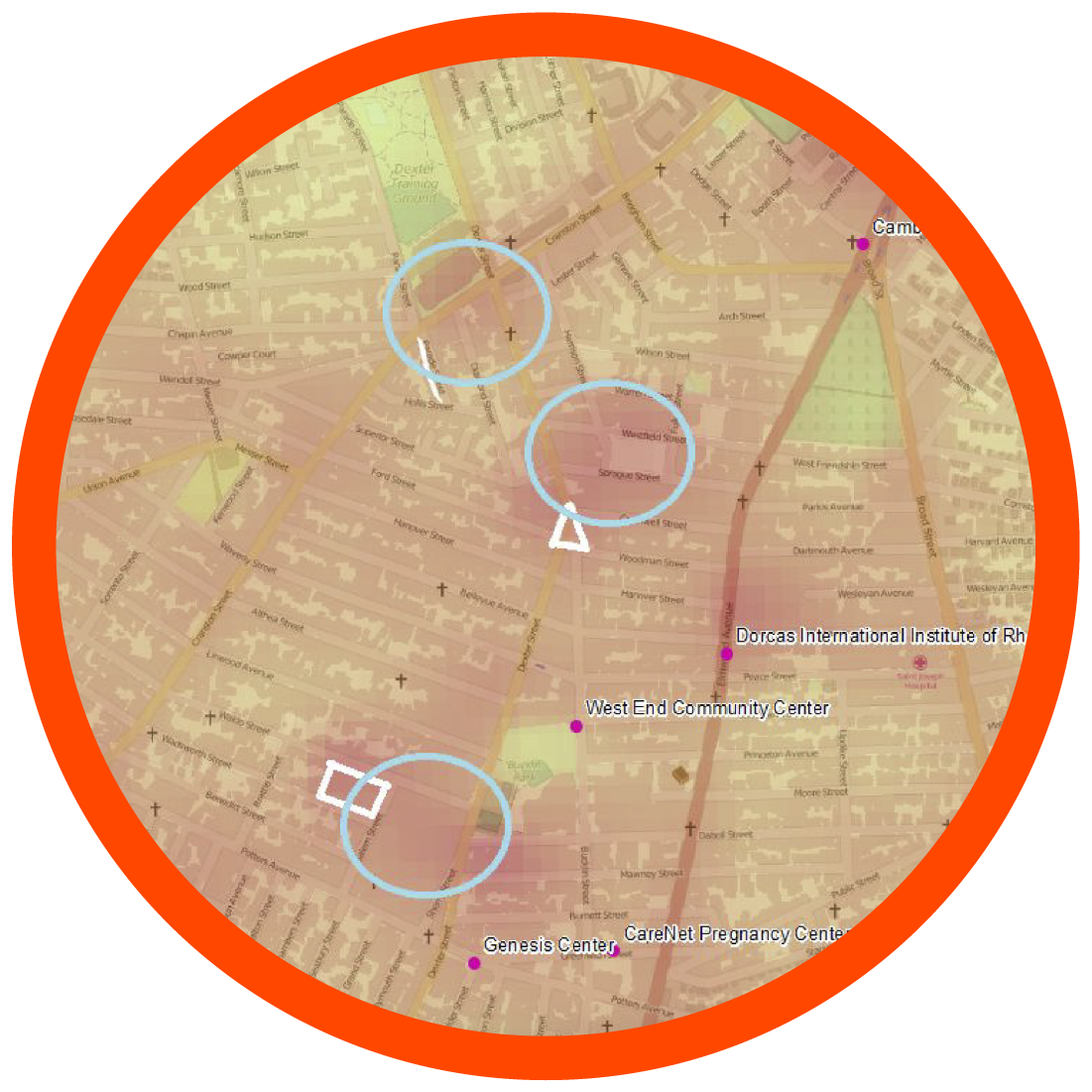

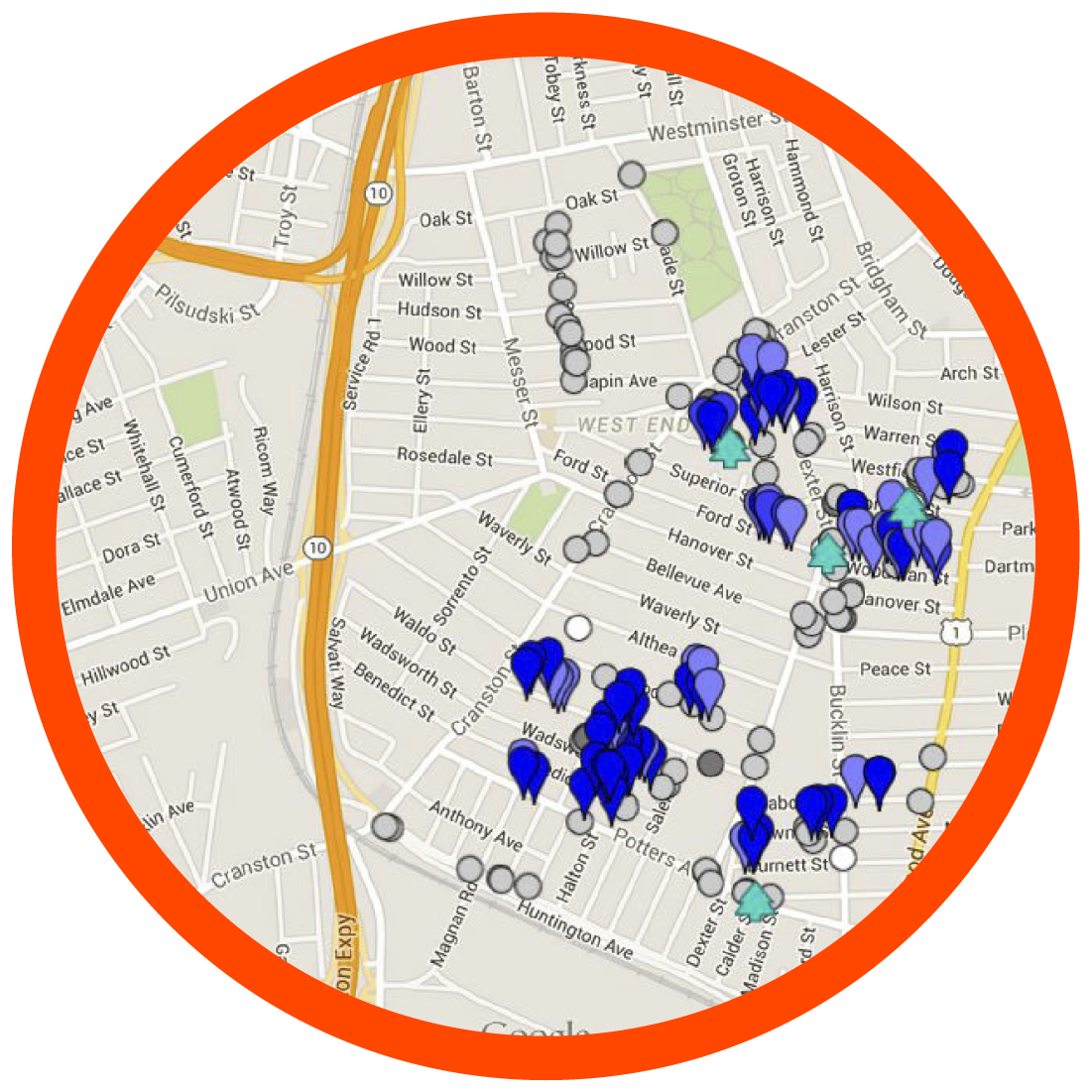

Map Data

The group analyzed GIS data including heat index, surface heat index, demographics, greatest need, surface pavement percentage, impervious surface cover, and tree cover to select a site.

"We overlaid impervious surface cover with a Landsat snapshot of surface heat index. After overlaying that, we circled a few sites where there were underserved demographics, where there were a heat islands, and where there was a lot of impervious surface cover." — Janice

-

Canvassing

The team collected anecdotal evidence by speaking directly with members of the community, including both businesses and households in the area.

"We really got to know the residents: we went to farmers’ markets and to the West Elmwood Housing Development. We tried to set up focus groups and just talk to as many people as we could. We walked the neighborhood almost every single day." — Kai

-

Synthesis

Combining quantitative map data and qualitative data from community surveys and focus groups gave the team a sense of where they had the most community support and could make the most impact.

"We turned the qualitative data, observational data, as well as canvassing data into mapping points basically. So we used the map to observe patterns in the point data as well as the GIS heat maps." — Grace

Proposed Project

MAKING A RAIN GARDEN

The team proposed a green infrastructure intervention�in the form of a vegetated system to both capture �and manage stormwater. Additional anticipated positive byproducts of the proposed solution include neighborhood beautification, traffic calming, and community development.

Mouse over the overview below to view the current state of the site and the proposed intervention:

To visually communicate their concept to community partners and their Brown TRI-Lab program cohort, the team mocked up an anticipated version of what their green infrastructure intervention will look like. The new vegetated area can be previewed in the envisioned image of the future, visible on the right in the below images.

Challenges

OBSTACLES & SOLUTIONS

| IMAGE |

PROBLEM |

SOLUTION |

|

Problem: Soil Contamination

Grace: "This city is loaded with contaminants..."

Kai: "...from its industrial past."

Janice: "The biggest issue with soil contamination is you can’t build very �many sites for water catchment and that slow-cycling you create through infiltration systems..."

Grace: "...through watersheds." |

Solution: Asking Experts

Kai: Once we removed the concrete, we had no idea what we were going to find underneath it. So we contacted the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. The department said that based on Providence’s past, we should assume that there will be high levels of heavy metals. But based on the square footage of our proposed site, which is about a thousand square feet, they didn’t think the infiltration would be large enough to mobilize the contaminants and bring them into the groundwater. So they gave us the go ahead on that. Which was great, because we had been planning on removing all the soil and disposing of it as hazardous waste and putting a cap at the bottom.

Grace: We still had to dispose of the soil.

Kai: But it was significantly less trouble than we thought. |

|

Problem: Existing Systems

Where preexisting systems have already been built, there are structural limitations to introducing new green infrastructure. A large percentage of yards are completely paved over in order to serve as parking due to the strict parking restrictions in Providence. Many homes and neighborhoods in the area had no grass or green space whatsoever. |

Solution: Working Within Constraints

The team identified vegetation that was suitable for the specific parameters of the site.

Kai: "We wanted to pick vegetation that would be hardy enough to survive the winters here, as well as survive being run over by cars, the salted roads. And then if we had to cap the soil then we couldn’t put in trees because of the root systems."

Janice: "The trees couldn’t have branches that would fall into the roads..."

Grace: "...or into people’s sight lines – you can’t have anything between 3 feet and 6 feet off the ground. We learned a lot about city permitting and coding through this project. And trees." |

|

Problem: Limited Data

Kai: "We tried to get a GIS layer that would show us where the storm drains on a street are, but they don’t have it. There’s no electronic data. There are maps from the 1800s of every street..."

Janice: ...hand drawn on canvas.

Kai: "But there’s no GIS data."

Grace: "And also you can take these maps out and look for a given storm drain, and it will be filled up with sediments."

Kai: "Some of them were growing trees!" |

Solution: Maps and Anecdotes

The team worked to identify areas with an overlap between greatest need (most flooding) and areas of greatest community support. Based on heat index, surface heat index, demographics, need, surface pavement percentage, impervious surface cover, �and tree cover, the team identified sites of interest.

They supplemented quantitative evaluations with anecdotal data.

Grace: "In some ways the things we heard from the organizations we were working with – like this intersection is the problem – were maybe more reliable." |

|

Problem: Budget Limitations

Developing a longterm solution requires cooperation and funding.

Janice: "Throughout the whole thing, maintenance was something that city officials and community organizations emphasized over and over again because that’s something that you really have to get – people who can continuously provide support – especially in the first year or two. Regular watering and weeding is generally required, and even after that there’s periodic making sure traps aren’t filling up."

Grace: "Even personal buy in is not a long term solution…you really need a funded institution that is not going to go anywhere. And this is why we have government." |

Solution: Fundraising

Janice: "We collectively raised about $14,000 total. �$5,000 of that was from Tri-Lab, $3,500 was from a grant that Groundwork Providence got and almost $5,000 was from the Department of Health."

Grace: "Labor is going to be donated by Groundwork Providence through their work program this spring, which is a huge cost we didn’t have to account for. We also set up donations for vegetation to cut costs and donations for a backhoe from the city to cut costs."

Kai: "We have a contract with Ground Work to do this work for us, and the money will be transferred to them." |

|

Problem: Engineering Plans

Grace: "In order to get engineering plans permitted by the city, you need to get a permitted engineer to sign off on them."

Janice: "Stamp of approval."

Grace: "Normally, it would have taken a long time and a lot of money to have an engineer sign these plans for us." |

Solution: Stamp of Approval

Grace: "We knew what we wanted, and we had done enough research – we eventually decided on a plan, and John Ford is an incredibly great, environmentally conscious engineer... "

Kai: "...who we had worked with over the summer so we weren’t totally cold calling."

Grace: "He took a look and gave it his stamp of approval eventually. It is now a real official engineering plan."

|

TakeawayWORKING WITH COMMUNITY

Although the project is on hold due to new obstacles in terms of finalizing permits, the team remains optimistic. The TRI-Lab experience proved to be a lesson in community engagement, environmental intervention, and working with stakeholders. The team emerged from the project with a key insight:

"One of the reasons I think our project was pretty successful…was because we had this direction �from the community organizations from the �beginning, and that was a stated need that made �us feel a little bit more like there was a reason for us �doing it and also sustained the project. That’s a key part of community-based participatory research, which is one of the things we studied…is that projects and especially projects from students need to come from a stated need of the community."

"One of the reasons I think our project was pretty successful…was because we had this direction �from the community organizations from the �beginning, and that was a stated need that made �us feel a little bit more like there was a reason for us �doing it and also sustained the project. That’s a key part of community-based participatory research, which is one of the things we studied…is that projects and especially projects from students need to come from a stated need of the community."

- Grace Molino